The current economic environment of burgeoning fiat (government-backed) currencies and near-zero (or negative) interest rates has revived gold’s attraction as an investment option. This white paper explores the historical link between gold and the U.S. dollar, provides a contemporary context for the metal’s recent resurgence, and charts a path for its future.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF GOLD IN THE U.S. MONETARY SYSTEM

For more than one hundred years—particularly during periods of global monetary shock—gold has offered universal comfort to the world’s economies. To understand its modern-day significance, we must consider gold’s historical relationship with the dollar.

During the mid-nineteenth century, the U.S. monetary system operated on a true gold standard, meaning, the value of U.S. currency or paper money was directly linked to the value of gold. Under this standard, a fixed price for gold is set and that price is used to determine the value of a country’s currency. (For example, if the U.S. sets the price of gold at $500 an ounce, the value of the dollar would be 1/500th of an ounce of gold.) Under this system, the growth of U.S.-denominated notes rises only to the extent that the value of gold stock increases.

HISTORICAL IMPACTS ON THE GOLD STANDARD

History has shown that during inflationary times, strict adherence to a gold standard is difficult to maintain. Through the occurrence of national and world events (such as wars and economic crises), the idea that dollar growth could be confined to the growth in gold became unrealistic.

U.S. Civil War

During the U.S. Civil War, the link between gold and “greenbacks” (as the dollar was known at the time) was temporarily suspended when war-related expenses caused an increase in U.S.-denominated notes, outpacing the growth and availability of gold. The link was later restored as a result of the Specie Payment Resumption Act of 1875, triggering what became known as the “Great Depression of the 1870s.”

After specie resumption was solidified in 1879, the gold premium to greenbacks ratio fell to par, with the appreciated greenback promoting confidence in the gold-backed dollar (Rothbard 2005, 160). From 1879 to 1914, the gold standard was implemented and most industrial countries, including the United States, were firmly linked to gold.

World War I

World War I, the first major war to occur since the reinstatement of the gold standard, once again put this monetary system in jeopardy. At the war’s onset, most European countries’ inflation rates were significantly higher than the U.S. inflation rate, causing those countries to abandon the gold standard. Indeed, throughout World War I, the U.S. dollar was the only major currency that remained convertible to gold. When the war ended, the U.S. emerged militaristically and economically more powerful than any other country at the time.

Following World War I, many European countries tried to reinstate the gold standard at their prewar ratios; however, this undertaking proved difficult and costly to maintain. By 1931, most major European countries had once again rejected the gold standard.

The Great Depression

During the Great Depression in the U.S., bank failures frightened the public into hoarding gold. In 1933, aware that one of the best ways to fight off an economic downturn is to inflate a government’s money supply, President Franklin D. Roosevelt used gold to do just that. Roosevelt knew that if the amount of gold held by the Federal Reserve could be increased, the Fed’s power to inflate the U.S. money supply would grow as well.

To prevent a run on American banks, Roosevelt declared a nationwide bank moratorium and forbade banks from paying out or exporting gold. Through Executive Order 6102, (also known as the Gold Confiscation Act), he ordered citizens to return all gold coins, gold bullion and gold certificates in denominations of more than $100 to the Federal Reserve in exchange for other money. He set the price of gold at $20.67 per ounce. Within ten days, $300 million in gold coins and $470 million in gold certificates had been returned.

In 1934, the government price of gold was raised to $35 per ounce, increasing the amount of gold on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheets by 69 percent and allowing the Federal Reserve to further inflate the U.S. money supply. Executive Order 6102 remained in effect until 1974, when President Gerald Ford repealed the limitation on gold ownership, allowing American citizens to once again buy and sell gold.

World War II

In 1944, toward the end of World War II, world leaders met to discuss a more permanent international monetary arrangement that would end the cycle of deflation-to-inflation-to- hyperinflation that had plagued much of the world in the previous seventy-five years. This arrangement, known as Bretton Woods, obligated member countries to convert foreign official holdings of their gold at certain par levels. However, because most of the world’s gold was held in the United States, many countries simply pegged their currencies to the dollar, which made the dollar the world’s de facto currency.

Bretton Woods maintained itself until 1971 when U.S. President Richard M. Nixon officially abandoned the dollar’s linkage to gold. Consequently, most other countries’ currencies were allowed to float against the dollar, an arrangement that remains in place today. Since then, the purpose of gold in the world’s monetary system has evaporated.

WHERE GOLD STANDS TODAY

Although gold’s purpose as a monetary anchor disappeared in 1971, the metal has maintained its value during periods when the dollar has weakened relative to other currencies. As a result, during times of stress in the U.S. dollar, gold’s popularity tends to swing into favor.

Contemporary economics shows that, when adjusted for inflation, real interest rates are negative in many industrial countries, including the United States. Negative real interest rates (and negative nominal interest rates in some countries) have been difficult to understand, contributing to investors’ interest in acquiring and holding gold.

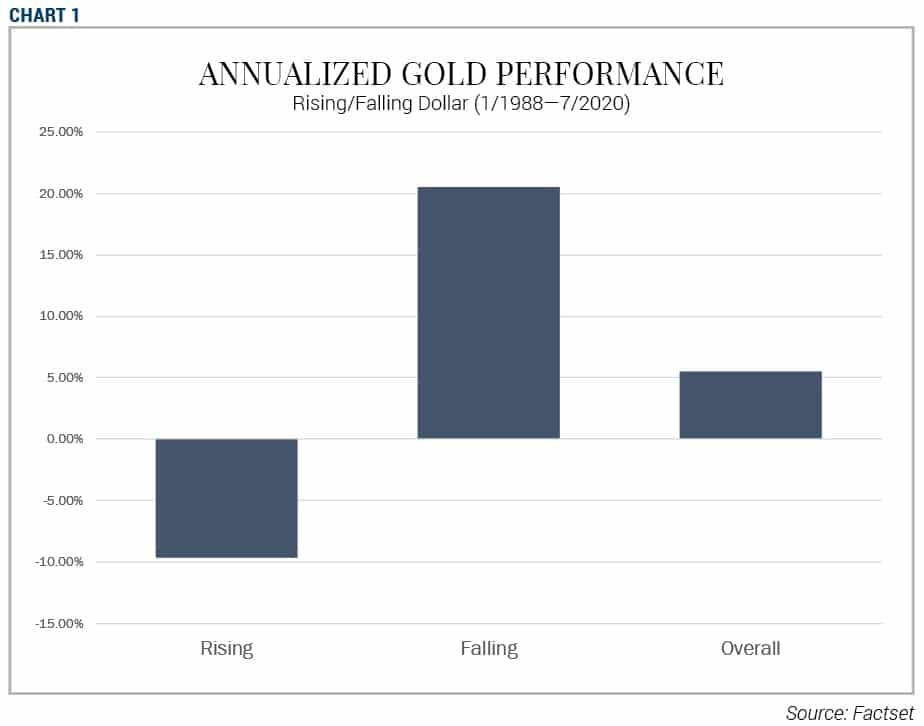

During periods when the U.S. dollar has fallen relative to a basket of currencies (a mixture of individual currencies used to set the market value of another currency), the price of gold has risen. When the dollar strengthens, the value of gold tends to fall. As a result, gold may not be the most attractive asset class for investment over the long-term (see Chart 1, above).

REASONS FOR DECLINE IN THE U.S. DOLLAR

Over the past fifty years, U.S. debt loads have been on an upward trajectory. Arguably, this track has recently become untenable as the U.S. government and other fiscal authorities implement extreme fiscal and monetary policies to counteract the negative economic impacts of COVID-19. Specifically, the U.S. government’s implementation of the largest fiscal response as a percent of all major countries’ Gross Domestic Product (GDP) underscores the U.S. dollar’s current weakness relative to a basket of industrial country currencies.

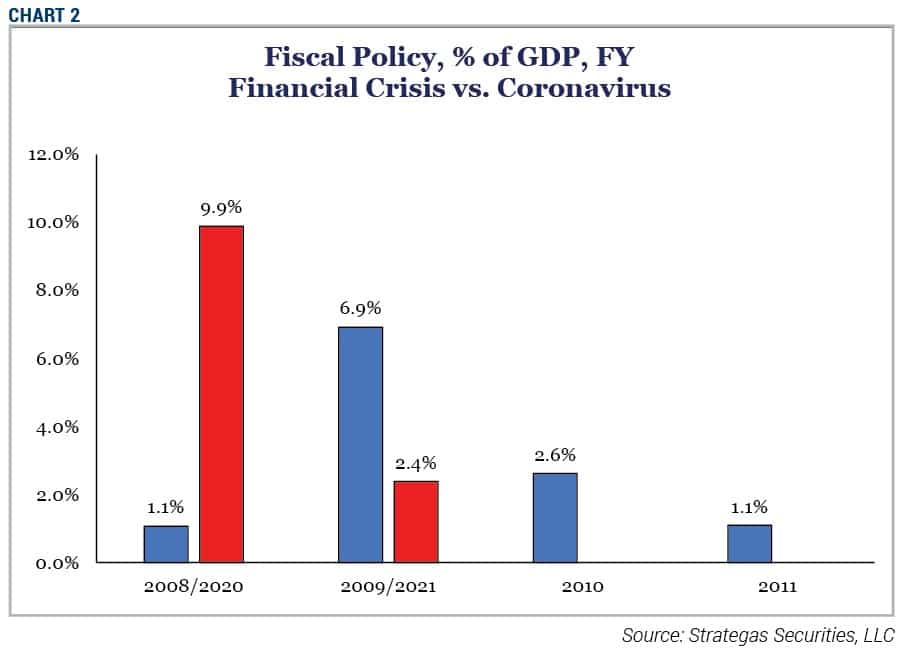

As Chart 2 illustrates below, to date, the U.S. fiscal response to the pandemic has amounted to 12.3% (with this percentage still growing) of GDP, far exceeding the 8% of GDP experienced during the 2008/2009 Great Financial Crisis. This stimulus, which was paid for with borrowed money, essentially expanded the U.S. monetary supply without providing a requisite increase in output.

Also playing a role in the U.S. dollar’s recent weakness is monetary policy. The Federal Reserve’s balance sheet—which is encroaching $7 trillion—is the largest in the industrial world. Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, the Fed’s balance sheet nearly doubled in the two months ending May 2020 as it expanded the quantitative easing program that was started during the Great Financial Crisis of 2008.

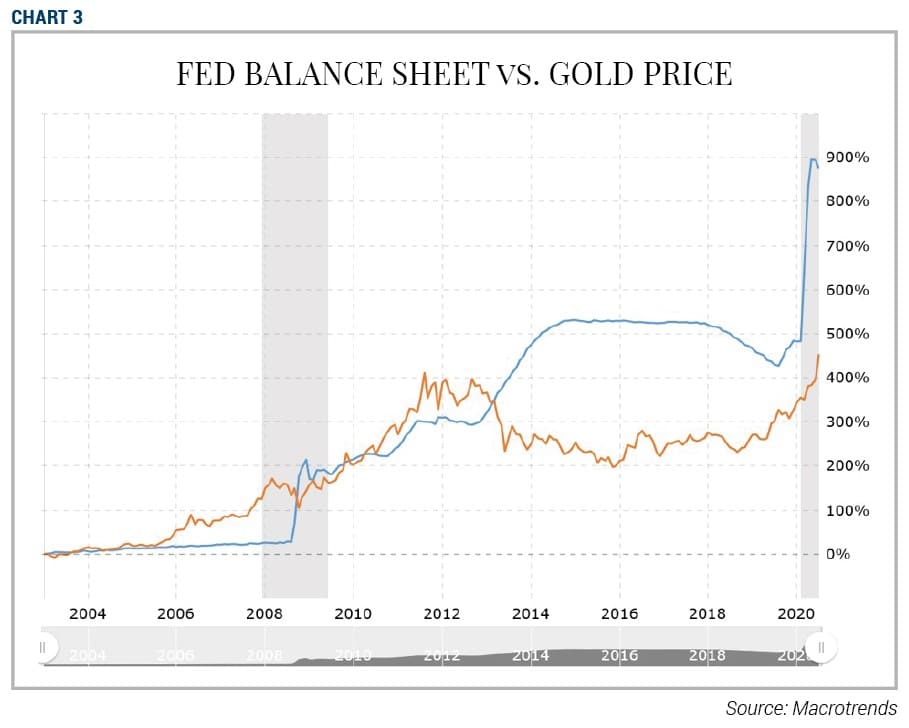

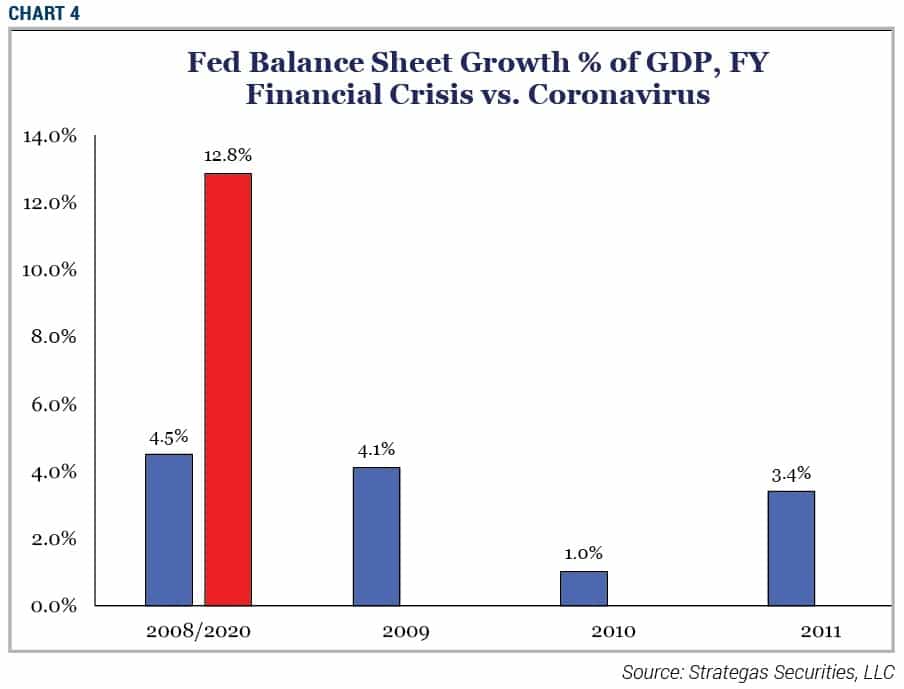

From 2009 to 2012, investors bid up gold from $700 to $1,800 a troy ounce as the Fed loaded $4 trillion onto its balance sheet. Presently, the U.S. is on track to exceed that number in two-thirds less time. Chart 3, below, illustrates the relationship of the price of gold to the Fed’s balance sheet during the Great Financial Crisis in 2008 and the current COVID-19 pandemic. Chart 4, also below, compares the Fed’s balance sheet growth percentage of GDP during the Great Financial Crisis in 2008 and the current coronavirus pandemic.

GOLD AND NEGATIVE REAL INTEREST RATES

Gold does not earn interest, therefore, historically, owners of gold have foregone the interest they could have earned on time deposits. However, with today’s interest rates at record lows, this trade-off becomes less of an issue.

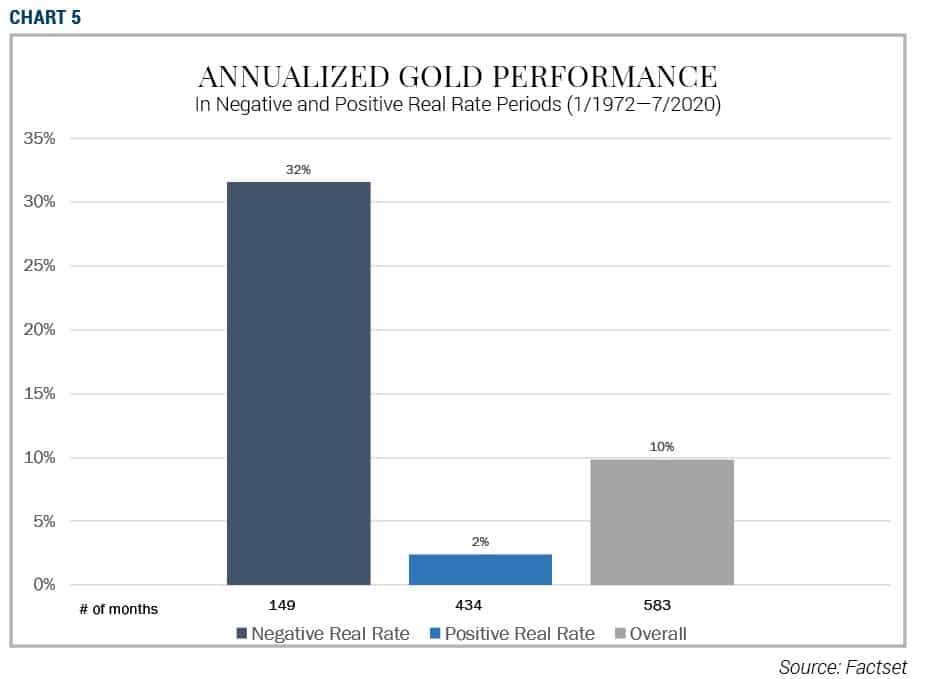

Despite gold’s price volatility, more investors are seeing value in holding a zero-yielding gold bar over a zero-yielding dollar bill. In addition, when adjusting for inflation, real interest rates are actually negative (see Chart 5, below).

WHERE WILL GOLD GO FROM HERE?

To determine what the future of gold might mean for investors, we’ve provided both near-to-intermediate term and long-term outlooks.

NEAR-TO-INTERMEDIATE TERM OUTLOOK

The near-to-intermediate term outlook for gold is promising. A declining U.S. dollar and today’s minuscule interest rate levels are symptomatic of current socio-political and economic conditions that are likely to persist as the world struggles through the COVID-19 pandemic and central banks experiment with untraditional monetary policies.

Meanwhile, the future of negative real interest rates and outsized central bank balance sheets is uncertain. As economic conditions normalize post-virus, unwinding many of these policies will be challenging. With trillions more cash dollars in the system than in pre-COVID levels, inflation risk is also a concern. Although gold holds no purpose as a medium of exchange, the practical and political difficulties that stand in the way of abandoning gold seem insurmountable (Bernstein 2008, 213).

LONG-TERM OUTLOOK

In 2021, fifty years will have passed since President Nixon abandoned the gold standard. This anniversary may seem meager compared to the 100-year post-Industrial Revolution relationship of the U.S. dollar to gold. During that time, however, modern technology has rapidly advanced.

Banking and finance industry innovations such as electronic payments and cryptocurrencies are indicative of a digital revolution that is moving beyond traditional boundaries. Even if the global monetary system evolves to form a new paradigm that doesn’t utilize the U.S. dollar as its central component, gold will continue to battle with new and existing currencies such as Bitcoin, the Euro, or the Chinese renminbi.

Gold’s long-term outlook is fraught with obstacles, but it will always remain a sentimental relic. As such, there will be periods when the value of gold gets bid up emotionally. Currently, we are experiencing one of those times. Investors may be tempted to profit from these emotional phases by adding gold to their portfolios. However, these phases are transitory and will pass.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Historically, gold has been used primarily as an alternative form of money rather than an investment option. Unlike traditional commodities like corn or oil, gold has an infinite shelf life and cannot be consumed. In addition, unlike stocks, bonds or real estate, which are assets with cash flows associated with them, gold yields nothing. Indeed, its yield is negative because it costs money to safely store gold. Consequently, gold can’t be valued using metrics typically applied to other assets.

In an extreme economic environment where depositors are earning little or no interest, however, the negative carry of gold goes away, making this metal attractive to investors. Even so, this doesn’t mean that gold is a safe investment as measured by price volatility. In reality, it can be as risky as equities. In fact, gold returns haven’t come close to equity returns. Any claims that position gold as the “ultimate safe asset” simply aren’t true.

While there may be periods when owning gold can be advantageous, it isn’t recommended as a long-term investment strategy. Permanent investment holdings should always be backed by strong fundamentals and the promise of future productivity. While gold may be an attractive tactical investment used to increase portfolio returns on a short-to-intermediate term basis, investors should question whether this relic should be utilized as a permanent long-term fixture in a portfolio.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aliber, Robert Z. The New International Money Game. 6th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

Bernstein, Peter L. A Primer on Money, Banking, and Gold. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2008.

Rothbard, Murray N. A History of Money and Banking in the United States: The Colonial Era to World War II. Auburn: Ludwig Von Mises Institute, 2002.

Any information, data, statements, opinions, or projections made in this article are the opinion of FineMark and may contain certain forward-looking statements, projections and information that are based on current beliefs of FineMark. No representation is being made that following this article and/or any information contained herein will or is likely to achieve profits. Although carefully verified, data is not guaranteed as to accuracy or completeness. The statements, opinions and/or data expressed in this article are subject to change without notice based on market and other conditions.

Investors should be aware that while gold and silver is used to preserve wealth by investors around the world, and may be considered “safe havens” based on investor perception that an asset’s value will hold steady or climb even as the value of other investments drops during times of economic stress. Perceived safe-haven assets are not guaranteed to maintain value at any time. Precious metals markets have historically experienced extended periods of flat or declining prices, and you may never experience a profit. Precious metals funds may be subject to greater volatility than investments in traditional securities. Investments in precious metals funds may be affected by overall market movements, changes in interest rates, and other factors, such as weather, disease, embargoes, and international economic and political developments.