Market Performance Overview

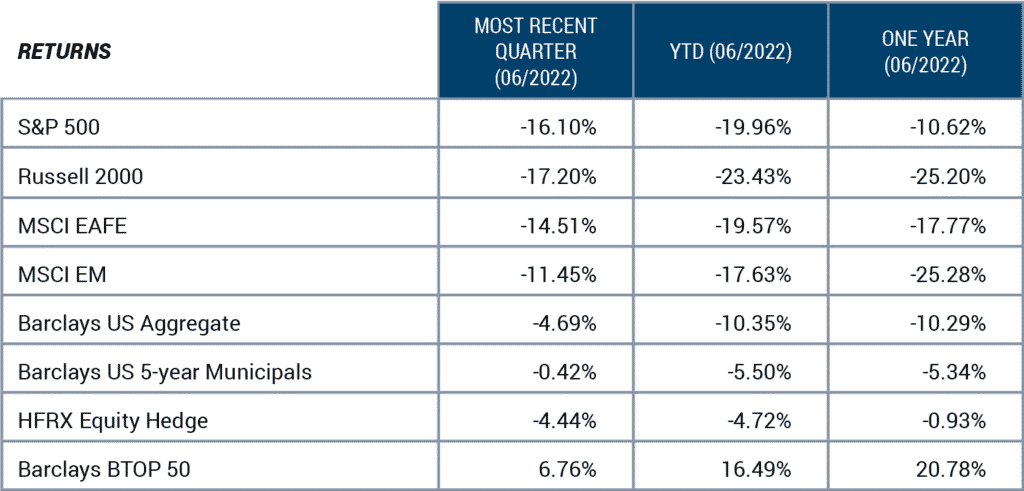

During the second quarter, global markets followed the downward trend that began in the first trading days of 2022. The S&P 500 posted a quarterly loss of 16.10% for the U.S. equity market, marking the first time since Q1 of 2009 that it has posted consecutive negative quarters. While historically it is not unusual to experience consecutive quarterly losses in equities, the 13-year hiatus left market participants complacent for this normal market phenomena. Notably, losses in equity markets outside the United States in both developed and emerging international markets occurred as well during this period.

Negative returns in bonds also continued with the Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index down 4.69%. When combined with bond market losses earlier this year and in 2021, the quarter’s drawdown in bonds is far worse historically than the loss in equities. In fact, the index hasn’t seen a value drawdown of this severity (11.7%) since 1980.

Considering the markets’ magnitude of losses, alternative strategies such as long/short equity and managed futures held up well. Managed futures were particularly strong, with short positions in bonds and equities, as well as long positions in the U.S. dollar (versus other major currencies) driving gains.

FIGURE 1

Source: eVestment

Historical Bear Market Performance Deciphered

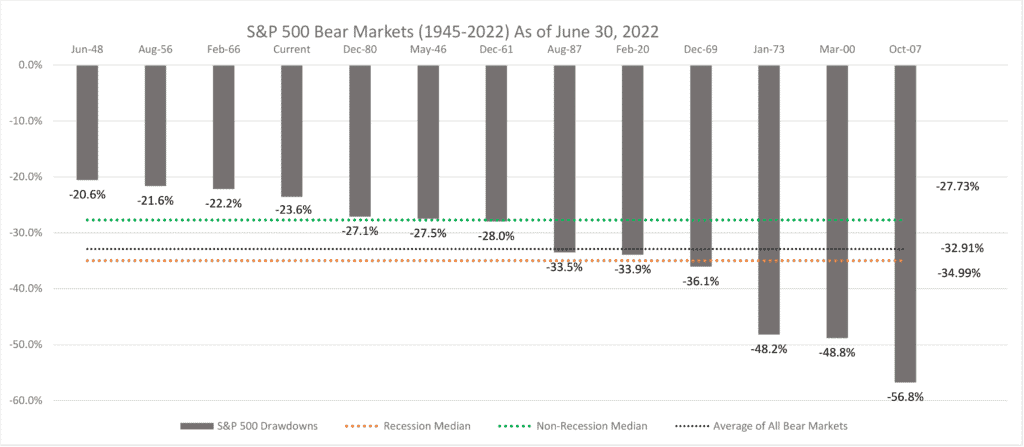

Second quarter 2022 losses were large enough for the S&P 500 to technically enter a bear market phase.

Even as the value destruction in equities has been unsettling and talk of a recession continues to stoke apprehension in investors, we encourage you to take a deep breath and remember, financial news outlets are inclined to sensationalize. And understanding how bear markets (defined as a drawdown of 20% or greater) have performed in the past can help us anticipate future market patterns.

From 1945 to today, the S&P 500 has experienced 13 bear markets. During the Quantitative Easing (QE) era, however, only one bear market occurred and it lasted just one month. And, as a result of the massive COVID-19 stimulus effort implemented by the Fed and Congress to spur economic activity, it was the shortest in history. We anticipate that in the new state we are entering where the cost of capital is normalized, markets will revert to a pattern where bear markets manifest every 4-6 years (as they have historically).

In Figure 2, below, we’ve assembled data on every bear market in the post-war era (12 total, excluding the current bear market). Of these, eight coincided with recessions and four did not.

FIGURE 2

Source: Factset Daily S&P 500 Price Returns

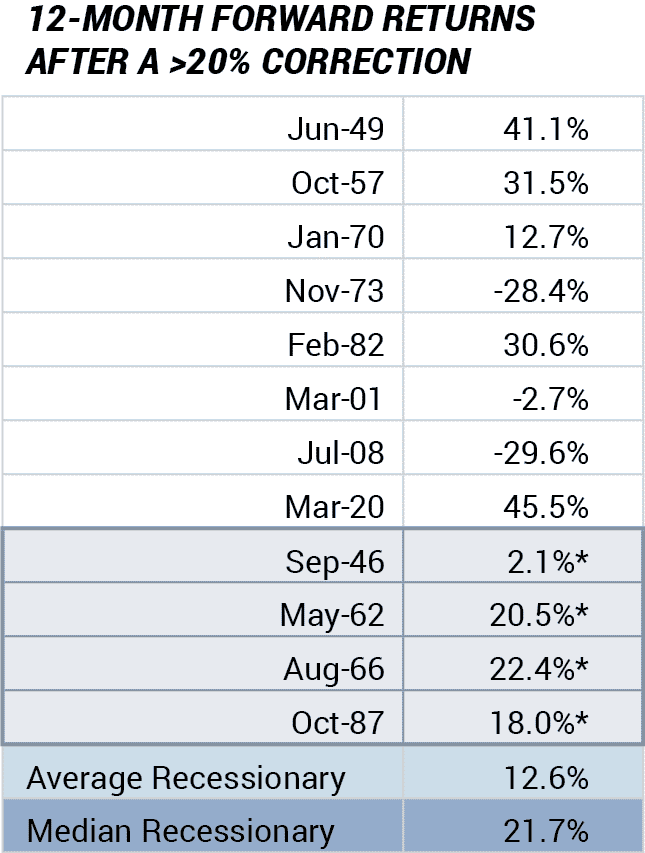

In Figure 3, below, we’ve compiled market-return data looking one year ahead, after the market has met the 20% bear-market threshold on the prior 12 bear markets. On average, the market is higher by 12.6% (or 21.7% on the median) 12 months after it enters a bear phase. We include both average and median computations in our analysis as extreme outsized observations can skew an average calculation, but not a median. We note that the non-recessionary periods experience stronger recoveries as the preceding drawdowns are also not as severe. To account for that, we took only recessionary periods into consideration for our average and median 12 month forward returns to paint a more conservative picture.

FIGURE 3

Source: Factset Daily S&P 500 Price Returns

*During non-recessionary Periods

Synthesizing this data, at -20% through the second quarter, we believe the market has already endured the majority of its losses. If history holds true, a year from today the market will likely be at higher levels. Keeping in mind that all of our client portfolios are individualized, our advice would be to refrain from selling equities at current levels unless your risk tolerance circumstances have changed.

Market Dynamics Shift

We believe that moving forward, we are entering a period of less stability as compared to the prior decade.

A major long-term shift is underway globally that may have significant, long-lasting effects on markets for the foreseeable future—far beyond the remainder of 2022.

This shift is driven by three primary factors:

- In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, energy sourcing options have become more challenging; global security risks have heightened, and military preparedness and western collaboration have been renewed.

- Nations are conducting retrospective supply chain examinations and enacting strategic diversification tactics.

- The Federal Reserve’s decision to move away from quantitative easing (QE), a monetary policy that allowed the Fed to reduce longer-term interest rates by purchasing Treasury and agency mortgages.

NATO’s Renaissance

“The purpose of the NATO alliance is to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.”

—The response of General Lord Hastings Ismay, the first Secretary General of NATO (1952-1957), when asked about NATO’s purpose.

As readers of our quarterly musings know, we often look to history for insight into what the future may hold. Since its founding in 1949, many had come to believe that the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a political and military alliance now composed of 30 member countries, had become a vestigial Cold War bureaucracy, no longer relevant in today’s world of globalization, peace and collaboration. Earlier this year, however, the organization received a new lease on life when Russia chose to shatter 75 years of European peacetime—the longest in history.

Since World War II, the world has lived in relative harmony, largely due to the security apparatus provided by the United States and NATO. In the years following the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, NATO’s relevancy has been questioned by many Americans, including former President Donald Trump, and other key NATO member states. This uncertainty was evidenced by the prolonged lack of funding from major Western European nations that were consistently below the 2% Gross Domestic Product target prescribed by NATO.

Acting on a perceived sense of apathy, in February, Russia saw an opportunity to expand its sphere of influence into Ukraine, a former Soviet satellite state. In hindsight, this decision has backfired, resulting in massive military support for Ukraine from the United States and the West. It precipitated further expansion of NATO’s alliance membership with the addition of two new states, Finland and Sweden. Interestingly, both countries remained neutral for the duration of the Cold War. It’s worth noting that Finland shares an 800-mile-long land border with Russia, which clearly weakens Russia’s hand from a strategic military perspective.

Moreover, Russia is the third-largest producer of energy in the world (following only the United States and Saudi Arabia). In the past, the bulk of that energy has gone to Europe. With Russia now in the world’s penalty box, other energy sources must be developed, resulting in higher global energy costs. Due to Europe’s prior dependency on Russian energy, these costs are currently being felt there disproportionately.

Deglobalization as Supply Chains are Reexamined

For the past 25 years or so, businesses have purposely moved production facilities to lower-cost offshore jurisdictions. Cost was seemingly the only factor companies considered when these decisions were made. The significantly lower unit labor cost advantage gained was massively disinflationary for U.S. consumers. Notably, China and other Asian markets benefitted most from this decision.

Now, as other factors are weighed into this equation (for example, there is the risk that a singular market will produce the bulk of high-end semiconductor chips), global supply chains are liable to shift and become more diversified. While this change will likely reverse the disinflationary trend experienced over the many preceding years, that turnaround will take years to culminate.

The End of the QE Era

During the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, the Federal Reserve enacted the QE monetary policy to prevent the United States from falling into a 1930s-style depression. Though well-intentioned, the policy brought inadvertent consequences including the rapid (and nearly uninterrupted) price rise of risky assets such as public equities, credit markets, and real estate. The QE policy also disproportionately benefited the rich, who own the majority of capital stock.

Conversely, current inflation rates have risen to levels the U.S. hasn’t experienced in over 40 years, causing a disproportionate negative impact on lower-income earners who typically spend a larger portion of their income on food, shelter, and energy.

To quell inflation levels, in March 2022 the Fed reversed the QE policy. This is not to say that QE will never reappear; rather, we believe it’s become an accepted monetary policy tool that could return if inflation were to fall below 2%.

No Matter the Season, We’re Always Here for You

When summer arrives, it’s not unusual for our clients in Arizona, Florida, and South Carolina to make a beeline for cooler locales. If you and your loved ones have northerly travel plans, please know we’re never far away. Whether you’d like to schedule a virtual meeting or have a quick chat on the phone, we’re available to answer questions or address any concerns that may arise while you’re away.

As always, we’re grateful for the trust you place in FineMark, are honored to act as the steward of your assets, and endeavor to earn that trust every day. Thank you for your continued support and faith in us.

2022 Second Quarter Review and Commentary

By Christopher Battifarano, CFA®, CAIA

Executive Vice President & Chief Investment Officer

Articles In This Issue:

SLATisfaction: Hedging your Federal Estate Tax Bets With a SLAT

Download 2022 Q2 Newsletter Here