Read and watch our latest review and commentary.

Listen as FineMark’s Chief Investment Officer, Chris Battifarano presents his first quarter market review with Private Wealth Advisor Gerry Roberts, followed by comments by Trust Administrator, Read Sawczyn on the ramifications of the CARES Act.

Read the newsletter below.

2020 First Quarter Review & Commentary

“I attribute my success to this – I never gave or took any excuse.” —Florence Nightingale (1820-1910)

The quote above is attributable to Florence Nightingale, who is credited with the founding of modern nursing techniques. While the bulk of this letter will discuss the economic and market ramifications of the coronavirus, we cannot ignore the human toll it is taking and want to begin by thanking all healthcare professionals, doctors, nurses, first responders, researchers, and others for their selfless dedication to their profession. The world critically needs their skills and knowledge. We are at the beginning of what will prove to be a long road in fighting the coronavirus, but we know that we will prevail in this crisis and come out of it stronger than ever.

In our last quarterly letter, we devoted substantial commentary to the very positive equity market appreciation that defined 2019 as well as the entire decade, measuring it against returns for prior decades dating back to the 1930s. A simple summation of that analysis is that the 2010s were a great decade to have been invested in equities, as equity market returns were far above average during that time period. Given where valuations stood at the end of 2019—and knowing that market returns tend to revert to the mean over time—we were cautiously optimistic about prospective returns over the next decade. But we clearly did not expect markets to deteriorate as quickly as they did in the first quarter of 2020.

In our last quarterly letter, we devoted substantial commentary to the very positive equity market appreciation that defined 2019 as well as the entire decade, measuring it against returns for prior decades dating back to the 1930s. A simple summation of that analysis is that the 2010s were a great decade to have been invested in equities, as equity market returns were far above average during that time period. Given where valuations stood at the end of 2019—and knowing that market returns tend to revert to the mean over time—we were cautiously optimistic about prospective returns over the next decade. But we clearly did not expect markets to deteriorate as quickly as they did in the first quarter of 2020.

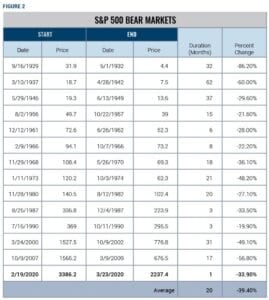

As illustrated in the table above, the market selloff was ferocious in degree and global in nature. Historically, bear markets develop on average over 10 months, however this bear market surfaced in just 16 trading sessions.

We are in the midst of a health threat unlike any we have seen in modern times. Some would describe the coronavirus as a “black swan” event (unpredictable), evoking Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s 2007 book, The Black Swan, in which Taleb describes a risk eerily similar to this one. We doubt Taleb would characterize the current crisis as entirely random and unpredictable. (If you have not read Taleb’s book, we would recommend it as a great way to spend some time during our continued days of social distancing.)

MARKET ALMANAC

Those of you who read our letter regularly know that we always look at history as a guide to what the future may hold. In this case, we will focus on two specific historical references average bear market duration and average bear market severity.

As you can see in Figure 2, in the past 90 years, the average bear market has declined by 39.4% and lasted 20 months. Within the context of the current market crisis, this data would indicate that the S&P 500 Index should bottom in October 2021 at a price level of approximately 2,052. To be clear, the end of a bear market does not mean the market has reached a new high, only that it has risen by 20% from its trough level.

As you can see in Figure 2, in the past 90 years, the average bear market has declined by 39.4% and lasted 20 months. Within the context of the current market crisis, this data would indicate that the S&P 500 Index should bottom in October 2021 at a price level of approximately 2,052. To be clear, the end of a bear market does not mean the market has reached a new high, only that it has risen by 20% from its trough level.

Another way to determine where markets might ultimately settle is through valuation. The most commonly used stock market valuation metric is the price-to-earnings ratio (P/E). Over the past 35 years, the S&P 500 Index has on average traded at 15x earnings. Currently, analysts’ earnings estimates for the next 12 months average around $172 per share. We believe this number is very optimistic, as earnings were approximately $163 per share in 2019. We feel it is unrealistic to assume any growth in earnings in 2020 given the current environment. We are more comfortable using an EPS figure closer to $139, which would indicate the market is trading on about 18x earnings as of April 3, 2020. If the S&P 500 were to revert to its historical average of 15x earnings, the index would be trading at around 2,100. So, by both the historic bear market approach and the historic P/E ratio method, it is not inconceivable that the S&P 500 could trade at levels of approximately 2100.

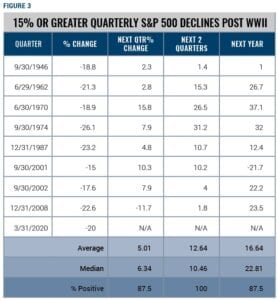

We are providing these market index levels and dates not as firm predictions, but instead what the future could hold based on how markets have behaved historically. Because this market sell-off developed much faster than average, it might abate more quickly and be less severe if the market can see through the economic uncertainty the virus presents. Historically, the market, a forward looking discounting mechanism, bottoms four months prior to the economy coming out of recession. In Figure 3 you can see how markets have generally recovered rather quickly from significant sell-offs. In the analysis above, which includes all periods after WWII, the next two quarters cumulative performance has been positive in every instance and has been positive in seven out of eight years after the drawdown. So, it is possible that the worst of this drawdown is behind us. Understanding the past enables us to make more intelligent and informed decisions about the future.

We are providing these market index levels and dates not as firm predictions, but instead what the future could hold based on how markets have behaved historically. Because this market sell-off developed much faster than average, it might abate more quickly and be less severe if the market can see through the economic uncertainty the virus presents. Historically, the market, a forward looking discounting mechanism, bottoms four months prior to the economy coming out of recession. In Figure 3 you can see how markets have generally recovered rather quickly from significant sell-offs. In the analysis above, which includes all periods after WWII, the next two quarters cumulative performance has been positive in every instance and has been positive in seven out of eight years after the drawdown. So, it is possible that the worst of this drawdown is behind us. Understanding the past enables us to make more intelligent and informed decisions about the future.

NEAR- AND LONG-TERM EFFECTS

We are loath to utter the most dangerous words in the investing world, “This time it’s different.” Yet we know of no other time in history when global governments purposefully shut down their economies to protect their citizens from a health crisis. The efforts of governments on all continents to prevent the spread of disease and “flatten the curve” of the coronavirus included using war-time powers to institute social distancing. The economic effect has been a massive global demand shock. The last time the world saw a global flu pandemic like this was a century ago when the Spanish flu ravaged the world. It claimed the lives of approximately 50 million people at a time when the global population was approximately 1.5 billion. Our superior medical knowledge and understanding of how viruses spread will certainly help us have a less tragic outcome with COVID-19, but the impact will still be substantial economically.

In the near term, the coronavirus will be deflationary, as it will cause a severe recession globally. Recessions by their nature are deflationary, and this one will be no different. We have already begun to see these effects in U.S. initial jobless claims data, which reached two, consecutive record-breaking levels, 3.3 million jobless claims for the week of March 20 and 6.6 million for the week of March 27. The total U.S. labor force consists of approximately 160 million people. Given the losses we have seen to date, as well as the severity of the contraction thus far, we expect the U.S. unemployment level to rise to the low- to mid-teens as further jobless claims are reported.

We believe that the coronavirus pandemic will be a watershed event, paralleling September 11, 2001 or the fall of the Berlin Wall. People will have a different view of life after COVID-19. One seemingly obvious consequence of this pandemic will be the de-emphasis of globalization, specifically with respect to China. If last year’s U.S.-China trade war did not prompt multinationals to rethink their supply chains, the coronavirus pandemic has certainly done so. The benefits of globalization include lower product costs, higher standards of living, and the spread of innovation, so deglobalization will have some negative effects. We envision a diversification of supply chains and possibly more manufacturing in higher-cost areas such as the United States and Europe as a result.

Bigger government could be another major consequence of this crisis. This has seemingly already taken hold with the passage of the $2.1 trillion CARES Act and likely will grow larger depending on how long the crisis persists. The federal government is getting much more involved in determining which businesses will receive federal aid and ultimately may have to nationalize (however one defines that) a number of “strategic” industries.

In addition, it is likely that we will see more widespread access to healthcare in the United States. Again, we have already seen some of this come to pass in the recently passed stimulus bill, which included a tax credit for two weeks of paid sick leave, a refundable tax credit for 10 weeks of paid family medical leave, and $8.3 billion in federal aid to develop vaccines and therapeutics to combat COVID-19.

We would also expect to see businesses and consumers use lower levels of leverage in the future. This will result in lower returns on equity for corporations and a reduction in consumer spending for individuals as they increase savings rates and defer spending on goods they can’t pay for in cash.

In summary, many of these effects of the coronavirus pandemic could lead to less productivity, higher rates of inflation, and greater government involvement in the economy.

CRUDE REALITY

In addition to the health concerns over the virus, the global economy is also dealing with a dramatic drop in the price of crude oil. Since the beginning of the year, the price of crude oil (as measured by West Texas Intermediate grade crude oil, or WTI) has fallen nearly 70%. As of 2019, the United States was the world’s largest producer of oil, larger than Saudi Arabia or Russia. But U.S. oil producers are not able to compete at the current price level, and this could have a significant contagion effect on the economy. In December 2019, the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas conducted a survey of executives at 93 oil and gas exploration and production firms. The survey indicated that 40% of firms could not sustain their capital expenditures with crude trading below $50 per barrel, while none of them said they would be able to sustain capex below $34 per barrel. At the time of writing, WTI currently trades for $29 per barrel. A combination of less exploration and production activity, higher rates of bankruptcies announced in the sector, and defaults on loan and bond obligations is expected as long as prices remain at these depressed levels. Currently there are negotiations underway between the US and both OPEC and non-OPEC members about possibly reducing some of the supply from the market.

WHEN AND HOW DOES THIS END?

Based on current estimates, the virus will peak during the second quarter. Since the virus started in China and spread throughout Asia before moving westward to Europe and then to North America, we look east to see what the future could hold.

Asian governments by now have begun to ease some of the restrictions on businesses and individuals. We believe the data out of China is unreliable and instead look to other countries such as Japan, South Korea, and Singapore for answers. Thus far, we see a gradual opening up for some businesses, while schools, museums, bars, and night clubs largely remain closed. To prevent new infections, these countries and others in Asia are implementing new border controls. These vary from country to country, ranging from barring foreign visitors entirely to requiring them to quarantine in government facilities and, in some cases, even requiring them to wear bracelets to track their whereabouts to confirm self-quarantine restrictions. In Singapore, many commercial buildings are instituting temperature checks before allowing people to enter. In restaurants and cafes, alternating seats are taped off to promote social distancing. Mass adoption of the use of masks in public places, which has been commonplace in Asia for years, may also take hold in the West. In fact, it may even be legally required as it was in parts of the United States following the outbreak of the Spanish flu.

In the United States, we expect to see continued economic contraction in the second quarter followed by a slow return to normal. Recovery should begin in the third quarter but will take some time to fully manifest; it may be a few quarters after that before we are back to where we started.

We do not see this developing into a 1930s-era economic depression as some have predicted. Again, we look at history as a guidepost. The U.S. is not committing the policy errors that were committed in the 1930s which included raising taxes, hiking interest rates, and starting a trade war with the passage of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in 1930. We see nothing like this today. Instead, we have seen swift and decisive action from the U.S. Federal Reserve and U.S. Congress to provide market liquidity as well as relief for businesses and individuals. We believe similar supportive actions will follow, possibly in the form of an infrastructure spending bill this summer. In our opinion, this is an appropriate policy response that strongly differentiates this period from the 1930s and provides the framework for a recovery.

FINEMARK IS READY TO SERVE YOU

As you have seen through our updates via email and on our website, we have taken a number of actions to safeguard our associates and our clients. These include limiting lobby hours, closing certain offices, and encouraging meetings via phone or video conference instead of in-person whenever possible.

Regardless of what additional measures we may need to take, we will not change our commitment to client service. We have migrated many of our associates to a work-from-home environment so that we can serve you safely during this period. We are proud to say that our phones will continue to be manned during normal business hours.

If there is anything you need, please call or email. In the meantime, for your safety, the safety of our healthcare workers, and the welfare of our nation during this period, please stay home and practice social distancing. We look forward to welcoming you back in our offices as soon as it is safe to do so.

2020 First Quarter Review and Commentary

2020 First Quarter Review and Commentary

By Christopher Battifarano, CFA®, CAIA

Executive Vice President & Chief Investment Officer

Articles In This Issue:

CARES Act and Your Retirement Plan

GRAT Planning Benefits from Low Interest Rates and Decreased Market Values

Download Full Newsletter Here